The rise of ChatGPT and its rivals is threatening the economic equilibrium on which the internet was built, writes The Economist.

Early last year, Matthew Prince began receiving disturbing phone calls from executives at major media companies. They told him they were facing a serious new online threat.

“I asked them, ‘Are they North Koreans?'” he recalls. “And they said, ‘No. It’s Artificial Intelligence.'”

Those leaders had noticed the first signs of a trend that is now clear: Artificial Intelligence (AI) is changing the way people navigate the internet.

As users turn to chatbots instead of traditional search engines, they get direct answers, not lists of web addresses to click on.

As a result, content publishers, from news media to forums and encyclopedias like Wikipedia, are facing alarming declines in traffic.

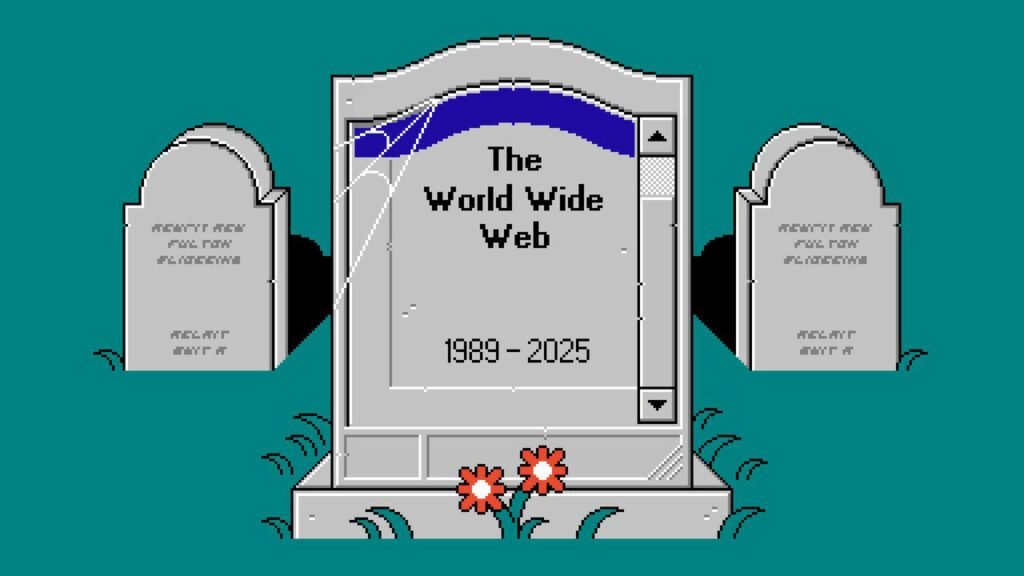

As AI changes the way users search for information, it is upending the economic arrangement at the heart of the internet. Human traffic, long generated revenue through online advertising; now, that traffic is drying up.

Content producers are urgently trying to find ways to force AI companies to pay for the information they use.

If they don’t succeed, the internet could turn into something completely different.

Since ChatGPT’s launch in late 2022, people have embraced a new way to search for information online. OpenAI, the company that developed the chatbot, says that about 800 million people use it.

ChatGPT is the most downloaded app on the iPhone AppStore. Apple said in April that traditional searches on Safari fell for the first time as users turned to AI. OpenAI is expected to launch its own search engine soon.

While OpenAI and other companies are growing rapidly, Google, which has about 90% of the US search market, has been adding AI features to its search engine to maintain its position.

Last year it began featuring “AI-generated summaries” before some search results, which have now become commonplace.

In May, it launched “AI mode,” a version of the search engine that functions as a chatbot.

The company now promises that, with AI, “Google searches for you.”

Users no longer visit the sites where the information is obtained.

But while Google “searches for you,” users no longer visit the pages from which the information is obtained. Similarweb, a company that measures traffic to more than 100 million websites, estimates that global human traffic to search engines has fallen by about 15% since June of last year.

Some categories, like entertainment portals, have fared better. But many others have been hit hard, especially those that once answered common search queries.

Scientific and educational sites have lost 10% of traffic, encyclopedia sites 15%, and health sites 31%.

For companies that rely on advertising or subscriptions, losing visitors means losing revenue. “We’ve had a very good relationship with Google for a long time…

“But they broke the deal,” says Neil Vogel, head of Dotdash Meredith, which owns magazines like People and Food & Wine. Three years ago, over 60% of their traffic came from Google.

Now that figure has dropped to about 30 percent. “They’re stealing our content to compete with us,” he says. Google insists that its use of other people’s content is fair.

But since the introduction of AI summaries, the percentage of news-related searches that lead to no further clicks has increased from 56% to 69%, according to Similarweb.

“The nature of the internet has completely changed,” says Prashanth Chandrasekar, head of Stack Overflow, a forum for programmers. “AI is choking the traffic for most content sites,” he adds.

With fewer visitors, Stack Overflow is seeing fewer questions posted. Wikipedia, which also exists thanks to the dedication of its contributors, warns that unreferenced AI summaries “block the path of access and contribution” to the site.

To maintain traffic and revenue, many major media outlets have launched licensing deals with AI companies, backed by legal threats, a strategy that Robert Thomson, CEO of News Corp, describes as “charm and lawsuit.”

His company, which owns the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, has reached an agreement with OpenAI.

Two of its subsidiaries are suing Perplexity, another AI engine. The New York Times has a deal with Amazon, but is also suing OpenAI.

There are also many other lawsuits and settlements in the works.

(The Economist Group has not yet licensed its content for training AI models, but has agreed to let Google use some articles for an AI service.)

But this approach has its limitations. So far, the courts appear to be on the side of AI companies: last month, two copyright cases in California were won by Meta and Anthropic, which argued that using content to train models is “fair use.”

Donald Trump also supports the thesis that Silicon Valley should have a free hand to develop the technologies of the future, before China.

He fired the director of the US Copyright Office after she said that the use of AI-protected content is not always legal.

AI companies are more willing to pay for ongoing access than for training data. But the deals reached so far are weak.

Reddit, an online forum, has licensed its content to Google for $60 million a year.

But its market value fell by more than half after it reported slower user growth, due to a drop in search traffic. (Growth has since improved.)

Stuck in the network

The biggest problem is that the vast majority of websites, hundreds of millions in number, are too small to lure or sue the tech giants.

Their contents may be collectively essential for AI companies, but each page is easily replaceable.

Even if they were to come together to negotiate as a group, antitrust laws prevent that. They could block the use of data by AI bots, and some have done so.

But this means they no longer have any visibility in search.

Software service providers can help. All new Cloudflare customers are now asked whether they want to allow AI bots to use their sites and for what purpose.

Cloudflare’s scale gives it a better opportunity than others to enable a collective response from sites that want to price AI searches.

A “pay-per-use” system is being tested that would allow sites to charge for bots to access. “We need to set the rules of the game,” says Prince.

According to him, the best outcome would be “a world where people get free content and robots pay a lot for it.”

An alternative is offered by Tollbit, which bills itself as a “bot paywall.” It allows sites to charge different fees for AI bots: for example, a magazine might charge more for new articles than for old ones.

In the first quarter of this year, Tollbit processed 15 million micro-transactions for 2,000 publishers, including the Associated Press and Newsweek.

Executive Director, Toshit Panigrahi, notes that unlike search engines that encourage repetitive content, charging for access encourages originality.

One of the highest rates for data usage is at a local newspaper.

Another model is proposed by ProRata, a startup run by Bill Gross, a pioneer of pay-per-click advertising in the 90s.

He proposes that money from advertising alongside AI responses be redistributed to sites in proportion to their contribution to content.

ProRata has its own search engine, Gist.ai, which shares revenue with over 500 partners, including the Financial Times and The Atlantic.

Although it is currently more of an example than a serious competitor to Google, Gross’ goal is to show a fair business model that can be copied by others.

Content producers are also rethinking their business models.

“The future of the internet doesn’t just depend on traffic,” says Chandrasekar, who developed Stack Overflow’s subscription product for businesses.

Media outlets are planning for a “Google-free” future, using newsletters and apps to reach audiences, and hiding content behind paywalls or at live events.

Dotdash Meredith says it has increased overall traffic, despite the drop from Google. Audio and video, for technical and legal reasons, are more difficult for AI to summarize than text.

The site where AI engines send the most traffic is YouTube, according to Similarweb.

Is the internet in decline?

Not everyone thinks the internet is in decline; on the contrary, it is in a “period of rapid growth,” argues Robby Stein of Google.

While AI makes content creation easier, the number of pages is growing: Google robots report a 45% expansion of the web in the last two years.

AI search gives people new ways to ask questions, for example, by taking a picture of their personal library and asking for recommendations on what to read next, which can increase traffic.

With AI questions, more pages than ever are being “read,” even if not by human eyes.

An answer engine can scan hundreds of pages for a single answer, using more resources than a traditional search.

As for the idea that Google is serving less human traffic than before, Stein says the company hasn’t seen any drastic drop in clicks, although it refuses to release that number.

There are other reasons why people may visit fewer sites: maybe they are using social networks.

Or they’re listening to podcasts.

The “death” of the internet has been warned before, by social networks, then by applications, but it has not happened.

However, AI may be the biggest threat to date.

If the internet is to survive in anything close to its current form, sites must find new ways to accept payments.

“People definitely prefer AI research,” Gross says. “And for the internet to survive, and with it, democracy and creators, AI research needs to share the revenue with creators.”

Source: https://monitor.al/en/It%27s-killing-the-internet–is-there-any-hope-of-saving-it/